Planetary scientists have discovered pieces of opal in a meteorite found in Antarctica, a result that demonstrates that meteorites delivered water ice to asteroids early in the history of the solar system. Led by Professor Hilary Downes of Birkbeck College London, the team announce their results at the National Astronomy Meeting in Nottingham on Monday 27 June.

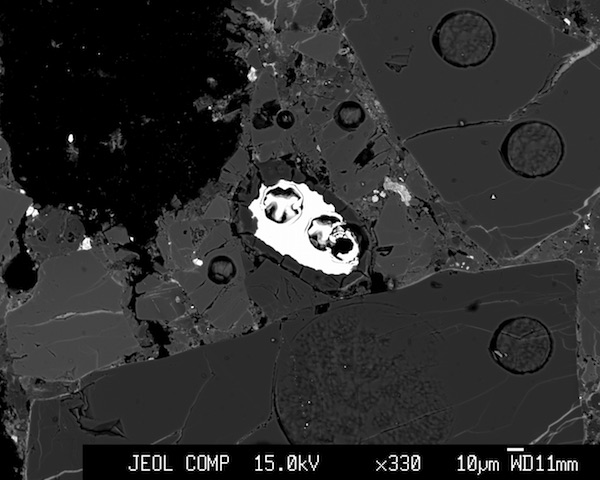

A backscattered electron image of the narrow opal rim surrounding a bright metallic mineral inclusion in meteorite found in Antarctica. The circular holes in this image are spots where laser analyses have been performed. Credit: H. Downes. Click for a full size imageOpal, familiar on Earth as a precious stone used in jewellery, is made up of silica (the major component of sand) with up to 30% water in its structure, and has not yet been identified on the surface of any asteroid. Before the new work, opal had only once been found in a meteorite, as a handful of tiny crystals in a meteorite from Mars.

A backscattered electron image of the narrow opal rim surrounding a bright metallic mineral inclusion in meteorite found in Antarctica. The circular holes in this image are spots where laser analyses have been performed. Credit: H. Downes. Click for a full size imageOpal, familiar on Earth as a precious stone used in jewellery, is made up of silica (the major component of sand) with up to 30% water in its structure, and has not yet been identified on the surface of any asteroid. Before the new work, opal had only once been found in a meteorite, as a handful of tiny crystals in a meteorite from Mars.

Downes and her team studied the meteorite, named EET 83309, an object made up of thousands and broken pieces of rock and minerals, meaning that it originally came from the broken up surface, or regolith, of an asteroid. Results from other teams show that while the meteorite was still part of the asteroid, it was exposed to radiation from the Sun, the so-called solar wind, and from other cosmic sources. Asteroids lack the protection of an atmosphere, so radiation hits their surfaces all the time.

EET 83309 has fragments of many other kinds of meteorite embedded in it, showing that there were many impacts on the surface of the parent asteroid, bringing pieces of rock from elsewhere in the solar system. Downes believes one of these impacts brought water ice to the surface of the asteroid, allowing the opal to form.

She comments: "The pieces of opal we have found are either broken fragments or they are replacing other minerals. Our evidence shows that the opal formed before the meteorite was blasted off from the surface of the parent asteroid and sent into space, eventually to land on Earth in Antarctica."

"This is more evidence that meteorites and asteroids can carry large amounts of water ice. Although we rightly worry about the consequences of the impact of large asteroid, billions of years ago they may have brought the water to the Earth and helped it become the world teeming with life that we live in today."

The team used different techniques to analyse the opal and check its composition. They see convincing evidence that it is extra-terrestrial in origin, and did not form while the meteorite was sitting in the Antarctic ice. For example, using the NanoSims instrument at the Open University, they can see that although the opal has interacted to some extent with water in the Antarctic, the isotopes (different forms of the same element) match the other minerals in the original meteorite.

Media contacts

Dr Robert Massey

Royal Astronomical Society

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877 699

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Ms Anita Heward

Royal Astronomical Society

Mob: +44 (0)7756 034 243

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NAM 2016 press office (from Monday 27 June to Friday 1 July)

Tel: +44 (0)115 846 6993

An ISDN line and a Globelynx fixed camera are available for radio and TV interviews. To request these, please contact Robert or Anita.

Science contacts

Prof Hilary Downes

Birkbeck College London

Mob: +44 (0)7711 463 536

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Images and captions

https://nam2016.org/images/nam2016/Media/Downes/Downes_opal_colour.jpg

Images of one of the many pieces of opal found in meteorite EET 83309. At top right is a backscattered electron image (the long thin dark object is opal). At bottom left is an image of silica concentrations in opal and surrounding meteoritic minerals. At top left is an image of oxygen concentrations in opal and surrounding minerals. At bottom right is an image nickel concentrations in opal and surrounding minerals. Credit: H. Downes

https://nam2016.org/images/nam2016/Media/Downes/Downes_opal.bmp

A backscattered electron image of the narrow opal rim surrounding a bright metallic mineral inclusion in meteorite found in Antarctica. The circular holes in this image are spots where laser analyses have been performed. Credit: H. Downes

Notes for editors

The RAS National Astronomy Meeting 2016 (NAM 2016) takes place this year at the University of Nottingham from 27 June to 1 July. NAM 2016 brings together around 550 space scientists and astronomers to discuss the latest research in their respective fields. The conference is principally sponsored by the Royal Astronomical Society and the Science and Technology Facilities Council. Follow the conference on Twitter via @rasnam2016

The University of Nottingham has 43,000 students and is ‘the nearest Britain has to a truly global university, with a “distinct” approach to internationalisation, which rests on those full-scale campuses in China and Malaysia, as well as a large presence in its home city.’ (Times Good University Guide 2016). It is also one of the most popular universities in the UK among graduate employers and the winner of ‘Outstanding Support for Early Career Researchers’ at the Times Higher Education Awards 2015. It is ranked in the world’s top 75 by the QS World University Rankings 2015/16, and 8th in the UK by research power according to the Research Excellence Framework 2014. It has been voted the world’s greenest campus for four years running, according to Greenmetrics Ranking of World Universities.

Impact: The Nottingham Campaign, its biggest-ever fundraising campaign, is delivering the University’s vision to change lives, tackle global issues and shape the future.

The Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) is keeping the UK at the forefront of international science and has a broad science portfolio and works with the academic and industrial communities to share its expertise in materials science, space and ground-based astronomy technologies, laser science, microelectronics, wafer scale manufacturing, particle and nuclear physics, alternative energy production, radio communications and radar. STFC's Astronomy and Space Science programme provides support for a wide range of facilities, research groups and individuals in order to investigate some of the highest priority questions in astrophysics, cosmology and solar system science. STFC's astronomy and space science programme is delivered through grant funding for research activities, and also through support of technical activities at STFC's UK Astronomy Technology Centre and RAL Space at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory. STFC also supports UK astronomy through the international European Southern Observatory. Follow STFC on Twitter via @stfc_matters

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS), founded in 1820, encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science. The RAS organizes scientific meetings, publishes international research and review journals, recognizes outstanding achievements by the award of medals and prizes, maintains an extensive library, supports education through grants and outreach activities and represents UK astronomy nationally and internationally. Its more than 4000 members (Fellows), a third based overseas, include scientific researchers in universities, observatories and laboratories as well as historians of astronomy and others.

The RAS accepts papers for its journals based on the principle of peer review, in which fellow experts on the editorial boards accept the paper as worth considering. The Society issues press releases based on a similar principle, but the organisations and scientists concerned have overall responsibility for their content.

Follow the RAS on Twitter